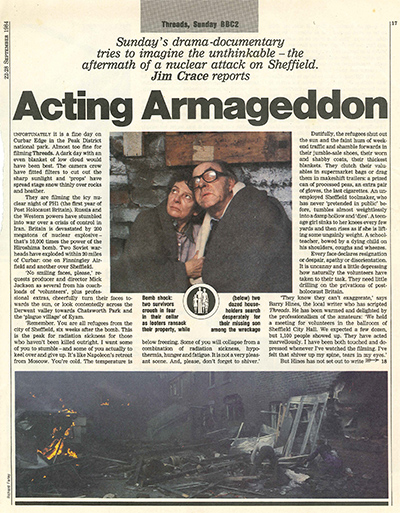

This is a copy of the article Acting Armageddon by Jim Crace, which first appeared in the Radio Times issue on Threads, 22 September 1984.

Sunday’s drama-documentary tries to imagine the unthinkable – the aftermath of a nuclear attack on Sheffield. Jim Crace reports

Unfortunately it is a fine day on Curbar Edge in the Peak District national park. Almost too fine for filming Threads. A dark day with an even blanket of low cloud would have been best. The camera crew have fitted filters to cut out the sharp sunlight, and ‘props’ have spread stage snow thinly over rocks and heather.

They are filming the icy nuclear night of PH1 (the first year of Post Holocaust Britain). Russia and the Western powers have stumbled into war over a crisis of control in Iran. Britain is devastated by 200 megatons of nuclear explosive that’s 10,000 times the power of the Hiroshima bomb. Two Soviet warheads have exploded within 20 miles of Curbar: one on Finningley Airfield and another over Sheffield.

‘No smiling faces, please,’ requests producer and director Mick Jackson as several from his coach-loads of ‘volunteers’, plus professional extras, cheerfully turn their faces towards the sun, or look contentedly across the Derwent valley towards Chatsworth Park and the ‘plague village’ of Eyam.

‘Remember. You are all refugees from the city of Sheffield, six weeks after the bomb. This is the peak for radiation sickness for those who haven’t been killed outright. I want some of you to stumble – and some of you actually to keel over and give up. It’s like Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow. You’re cold. The temperature is below freezing. Some of you will collapse from a combination of radiation sickness, hypothermia, hunger and fatigue. It is not a very pleasant scene. And, please, don’t forget to shiver.’

Dutifully, the refugees shut out the sun and the faint hum of weekend traffic and shamble forwards in their jumble-sale shoes, their worn and shabby coats, their thickest blankets. They clutch their valuables in supermarket bags or drag them in makeshift trailers: a prized can of processed peas, an extra pair of gloves, the last cigarettes. An unemployed Sheffield toolmaker, who has never ‘pretended in public’ before, tumbles almost weightlessly into a damp hollow and ‘dies’. A teenage girl sinks to her knees every few yards and then rises as if she is lifting some ungainly weight. A schoolteacher, bowed by a dying child on his shoulders, coughs and wheezes.

Every face declares resignation or despair, apathy or disorientation. It is uncanny and a little depressing how naturally the volunteers have taken to their task. They need little drilling on the privations of post-holocaust Britain.

“I’ve felt that shiver up my spine, tears in my eyes”

‘They know they can’t exaggerate,’ says Barry Hines, the local writer who has scripted Threads. He has been warmed and delighted by the professionalism of the amateurs: ‘We held a meeting for volunteers in the ballroom of Sheffield City Hall. We expected a few dozen, but 1,100 people showed up. They have acted marvellously. I have been both touched and depressed whenever I’ve watched the filming. I’ve felt that shiver up my spine, tears in my eyes.’

But Hines has not set out to write an emotional film. ‘It was my duty to be as even-handed and as objective as possible,’ he says. ‘This film must be as accurate as any film can be. People will not have seen a film which is as factual as this. A lot of people saw The Day After but they could disassociate from it because it portrayed an American experience. The War Game was good – but it is out of date now.’

It is difficult, in fact, to be up to date. Hines was continually having to revise his script as new information came to light. On this February day of filming at Curbar, a report has been released by the World Health Organisation. Its panel of experts, including scientists from London, Boston and Moscow, agrees that a one-megaton bomb dropped on London would kill 1.8 million people outright and, in the event of an all-out war (of approximately 10,000 megatons), ‘half the world’s population, more than 2.2 billion people, would be immediate victims’.

And – despite the cheery assertion of one St John Ambulance Brigade volunteer on duty at the filming that ‘I would have an important medical role after a war’ – most experts predict that no health service in the world could hope to function. And within days yet another report – this time from British farmers – describes agriculture after the bomb: the land ‘devastated by tidal waves’, grain supplies ‘decimated by looters’, weeds and insects (the best survivors, our natural heirs) re-possessing the ‘countryside’.

“The generation which followed ours would be brutal, stunted both physically, emotionally, and mentally”

‘There would be some survivors, of course,’ says Hines, carefully avoiding the exaggerated and unscientific prognoses which, he feels, have marred both sides of the nuclear debate (and which Threads hopes to balance.) ‘But many would have hideous, untreated injuries, and then there would be widespread radiation sickness and leukaemia. There could be a sort of Third World-cum-medieval peasant agriculture.

There would be barter, a relearning of old manual skills, a new language among kids because there wouldn’t be the standardising influences of schools, newspapers and television. And I can’t imagine loving parents. As soon as kids were big enough, they would have to work and fend for themselves. The generation which would follow ours would be brutal, stunted both physically, emotionally, ‘And mentally. . .’ adds Mick Jackson. While making his earlier Q.E.D. documentary, A Guide to Armageddon, he unearthed a plethora of scientific data which had not been generally available, not because it was secret but simply because it had been buried in learned journals. It mostly concerned the psychological impact of nuclear war: ‘There has been a rather optimistic belief maintained by officials in Europe and America that after the first few weeks survivors are going to come out of their shelters, gung-ho like the Seven Dwarfs with picks over their shoulders, and set off to work on the reconstruction of Britain.

‘But even after the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, when the Allies poured in money to rebuild the cities, there was no psychological improvement for the survivors. So you can imagine what it would be like in a global nuclear war when there would be no outside forces to provide assistance. We must expect profound and prolonged psychological damage.’

Even the ‘chosen few’ (those officials and top brass already named and designated to govern Britain in the PH years from their regional bunkers) cannot expect ‘ to remain psychologically intact – particularly if they have been stationed in the shelter under one city hall which has its only toilet situated on ground level! Both Jackson and Hines spent a week at the Home Office training centre for ‘official survivors’ at Easingwold in Yorkshire. ‘We sat in on one of their courses,’ says Barry Hines. ‘They set the participants up in control rooms and let them handle the survivors. We had our eyes opened on how disorganised it would all be. And we thought that the whole approach of these courses was over-optimistic. ‘But it has to be, doesn’t it? Breakfast, lunch and dinner – and every day a clean shirt. And plenty of plucky gallows humour, too, just like in the First World War.’ One man, remembers Hines, was a smoker and his colleagues delighted in pulling his leg: ‘Stub it out, old son. Smoking’s bad for you. You’ll never make old bones.’

“A barely suppressed disquiet”

But Hines sensed a barely suppressed disquiet at Easingwold – the participants understood that they were merely simulating war. But, in a real war, would they leave their wives and children for the limited safety of the bunkers? Would their teasing good humour survive the claustrophobic months of incarceration? Would they be fit to rule? ‘Some just shrugged the problems off and said, “It’ll never happen”,’ says Hines. ‘Others – and this is the most common response – said, “I don’t want to know about it. When it happens, let me be pissed and right underneath the very first bomb.” But as the course progressed they became more thoughtful. Nobody came out of that week unchanged.’

And none of the cast and ‘extras’, too, came out of filming unchanged. They had come as close, perhaps, as anybody in Britain to ‘experiencing’ a Third World War. Their faces caked with ‘radiation burns’ which have set thick and cold like the skin of custard, they are now filming a few miles to the east of Curbar Edge, at the appropriately named Spitewinter Farm. Its fields are newly rigged by ‘props’ with the antler trees of a defoliated forest. It is PHZ and time for the first, precarious harvest.

The fittest volunteers drag away the bales like working horses, while the weakest and sickest glean every scattered seed. A quarter of a mile away in the valley, the huntsmen are out with their hounds and their ‘pink’ livery. ‘I see the toffs are still having-a good time after the holocaust,’ jokes one of the extras.

Further in the distance, over what the city council has designated ‘Nuclear Free Sheffield’, the thin, soundless vapour trail of a Finningley jet decorates the sky.

Looking for more?

My book, Nuclear War in the UK (Four Corners Books, 2019) is packed with images of British public information campaigns, restricted documents, propaganda and protest spanning the length of the Cold War.

It also tells the story of how successive UK governments tried to explain the threat of nuclear attack to the public. It costs just £10 – find out more here.