This first blog post is on one of my pet topics, the myth and reality surrounding the Protect and Survive public information campaign. I’d welcome any feedback, especially if you spot any inaccuracies or omissions – drop me a line on Twitter.

“The average person, if given the choice of being blasted or frizzled on the one hand, or taking his chance of dying a lingering death from fallout on the other, would opt for the latter course every time…” – Home Office memo, 3rd September 1975

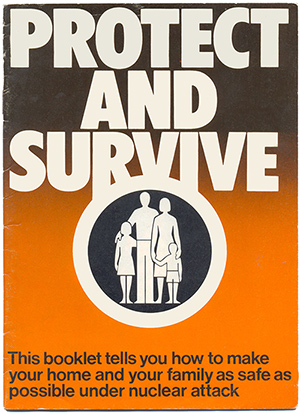

Protect and Survive is best known today as a 1980s pamphlet offering advice – bad advice – on protecting your family and property if nuclear weapons were ever used against the UK. Met with ridicule by a sceptical media, and derided in popular culture, Protect and Survive has been become lodged in the popular imagination as an unusual, unsettling and ultimately ineffectual campaign.

Influenced by the media, and reinforced by every retelling, a myth developed around Protect and Survive which has created a distorted, parallel version of the campaign. It has even led to false memories – people who claim they were frightened out of their wits by the pamphlet’s arrival in their letterbox, even though it was never actually distributed like that; people terrified by the broadcast of the animated films on TV (of which only extracts were ever shown). Of course, the myth built up around Protect and Survive is often quite far removed from the reality.

Despite looming large in early 1980s popular culture, very little has been done to actually examine or deconstruct Protect and Survive. In this series of blog posts, I’m going back to the origins of the campaign to present a better idea of where it came from, how it was developed, why it ‘went nuclear’, and why we remember it the way we do.

For context, I will take a quick look at the precursors to Protect and Survive. I’ll share the Home Office’s original aims in producing what they referred to as the “pre-attack mass information programme”. I will try to unpick the extent to which the authors believed the advice would be effective – or whether the campaign’s true purpose was hidden between the lines. And I’ll consider what impact the critical reaction to Protect and Survive has had on subsequent attempts to educate the public about preparing for the unthinkable.

Earlier campaigns

Protect and Survive was by no means the first campaign developed to educate and inform the public about nuclear attack. Pamphlets on the topic were published by the Home Office, usually prepared by the Central Office of Information (CoI), starting in the early 1950s. In order to properly understand Protect and Survive, it’s worth taking a whistlestop tour of the publications that led up to it (I plan to cover each of these in more detail in later posts on this blog).

The earliest, such as “Civil Defence and the Atom Bomb” (1952) are rooted in the Second World War, still fresh at that point in the public’s mind. With references to respirators, communal shelters and incendiary bombs, these early guides provide dubious reassurance (“in the city of Hiroshima, over half the people within a mile from the explosion are still alive” … “contamination is not likely to last long”) but are short on practical advice.

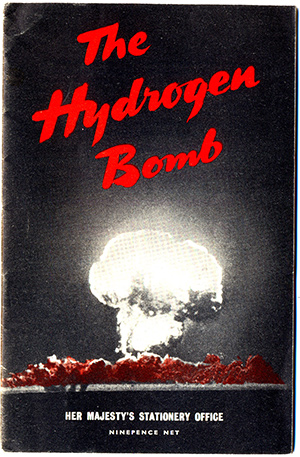

In 1957, the first substantial booklet was published on the topic, taking its title from the latest weapon in Britain’s nuclear arsenal: “The Hydrogen Bomb”. This booklet shed much of the previous Blitz-spirit optimism, presenting instead the cold hard facts. The danger from blast, the danger from radioactivity, fallout, and even radiation sickness were covered with a new level of honesty and directness.

The advice was updated in 1963’s pared-back and rather thinner “Advising the Householder on Protection against Nuclear Attack”, which was the direct precursor to Protect and Survive. This booklet was designed to educate public servants and volunteers who would advise their communities ahead of an attack, and focuses on explaining the basics of how a nuclear weapon works, shelter construction, gathering supplies, knowing the warning signals, and first aid. The booklet can be seen in Peter Watkins’ film The War Game, which is to the Advising the Householder booklet what 1982’s nuclear horror movie Threads is to Protect and Survive.

A new approach

In the context of these booklets, Protect and Survive was arguably quite innovative. While most people associate it with a simple booklet, it was actually conceived by the Central Office of Information, the government’s PR and advertising wing, as a full public relations campaign. In fact, the booklet was only ever intended to play a supporting role; the original campaign plan called for a “comprehensive radio and television campaign”, supplemented by a “basic handbook” and newspaper advertising. The intention was to “communicate essential information to the widest possible audience”, something made possible by broadcast media.

Plans for the campaign were first prepared in autumn 1975, with a view to having the final broadcast and print materials ready for use by March 1976.

In total, 20 short, modular films were created, narrated with authority by actor Patrick Allen, and produced by William Stewart TV Productions and Richard Taylor Cartoon Films. The latter had experience in working with the COI in animating other public information films, such as the 1973 Charley Says series of safety films for children – as well as being responsible for gentle TV cartoon series Crystal Tipps and Alistair.

Each film ended with an animated version of the protected family logo as seen on the cover of the booklet, together with a synthesised ‘musical logo’ composed by Roger Limb. (Limb, a member of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, would go on to become known for creating electronic music for 1980s episodes of Doctor Who.)

Getting the word out

A nuclear strike would not necessarily been a bolt from the blue – many optimistically predicted a period of heightening tension, followed by conventional war, leading up to nuclear attack. The creators of Protect and Survive certainly envisaged this scenario, with plans for a staggered broadcast of the films and radio tapes.

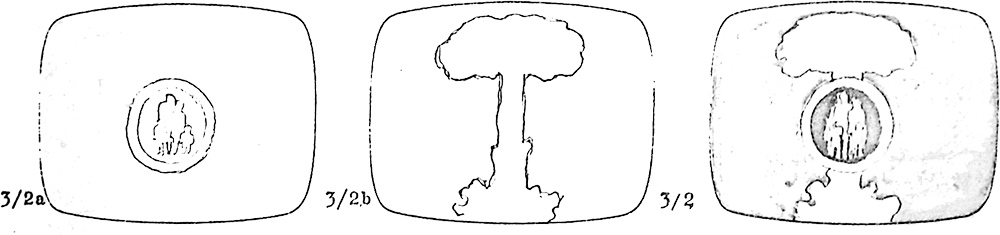

The idea was to show a first set of films in a “low-level crisis” – defined as weeks to months before attack – followed by a second set during the “preparatory period” as the likelihood of attack increased. The initial films covered the key information – what a nuclear explosion was, what warnings you’d hear, why it was important to stay at home; they explained the booklet, and outlined how to make a shelter.

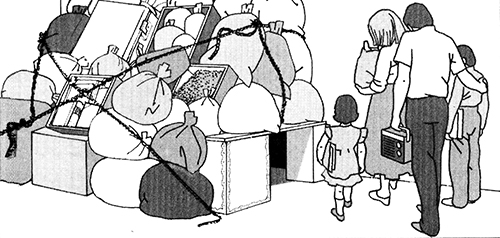

The second set of films was held back, presumably because the gritty detail the tapes went into would have been more likely to lead to panic. These films covered everything from how to provision your fallout room, to ‘sanitation discipline’, ‘life under fallout conditions’, and burials. They also instructed people that it was time to start building their makeshift fallout shelters.

If attack seemed likely – termed “probable inevitability of war” – all the films and radio broadcasts would be repeated. Radio tapes would be played alongside the films, reflecting the themes being broadcast on TV. Broadcast plans were not made for the period after hostilities began, for, as the campaign plan points out, “TV may not be available”; a later memo reiterates this, saying attack warnings would be broadcast on radio but “we are unlikely to have TV by that time.”

What about the booklet? According to a Home Office memo from October 1975, the booklet wouldn’t have been issued until “a relatively late stage in the crisis”, by which point people would be expected to already be making preparations. An internal memo explicitly states that there were no plans to release the booklet until absolutely necessary, “because it needed to be seen in conjunction with the rest of the publicity package, and the Department did not want to alarm the public”.

This serves to emphasise just how central the broadcast element was to the campaign – and how peripheral the booklet was. Of course, the Home Office had other reasons not to release the booklets too early. The cost of printing millions of 32-page booklets – at £550,000, more than five times the campaign’s budget – was clearly prohibitive. Distribution, estimated at a further £500,000, would have been hard to defend unless events were very clearly taking a turn for the worse.

A newspaper campaign, based on the content of the booklet, was also prepared. The content was laid out as two-page broadsheet and four-page tabloid inserts, and six sets of printers’ positives and negatives were created in readiness.

Did they really believe it would be useful?

The extent to which the authors of Protect and Survive believed their own advice would actually be useful is unclear.

We know what they thought of the preceding publicity material – Advising the Householder on Protection against Nuclear Attack. The Home Office’s emergency planning department, known as F6 Division, called it “misleading, difficult to follow, and outmoded in its presentation”.

We also know that the CoI wanted to test the impact of the campaign materials, to see how well people retained the information. Tests were to be “weighted in favour of the less able” by excluding anyone under 25, and only testing socio-economic groups C and lower. Narrowing the sample further, the materials were to be tested by employees of local authorities, “so that a certain level of co-operation is guaranteed”.

Worries about the potential for adverse publicity seep through. By taking the preferred route of testing with compliant council employees, it’s made clear that the local authorities selected “should be in full sympathy” with the central government line on civil defence. Not all local authorities toed the Westminster line: some urban councils, such as those in Sheffield, Manchester and Greater London, would go on to declare themselves ‘Nuclear-Free Zones’ in the early 1980s, so would not be good candidates. Nevertheless, it was recommended that P&S was to be tested across a range of rural and urban locations, as well as at least one place in Wales and one in Scotland, “to avoid bias”! In the end, the tests took place in Ealing, Sheffield, Edinburgh, Tonbridge in Kent and Shirehampton in Bristol (the closest they came to running a test in Wales) between December 3rd and 9th 1975.

An alternative proposal, to test the plans with a broader sample of the general public, is played down due to “a risk of publicity being given to the exercise” – a fear which an anonymous Home Office reviewer shares, pencilling “important point” into the margin. The Home Office did eventually accept that leaks would be inevitable, saying they would be prepared to deal with any criticism. The ‘restricted’ classification was removed from the project as it started to come together in October 1975, and press officers at the CoI’s regional offices were briefed.

As an aside, the original proposals for P&S are very much of their time. The plan says certain topics – such as gathering provisions – should be tested only among women, while others – such as building a shelter – should be tested only among men. To their credit, the Home Office reviewer has scribbled next to this suggestion: “Why? Women may have to do it”.

Six key videos were to be tested, along with six radio tapes, although each respondent would only experience a maximum of three films or four tapes. The booklet was to be tested, too, being given to the test subjects beforehand to swot up. A line of basic questioning would follow, to check how much knowledge had been retained, followed by a more general discussion.

It’s not clear how useful this testing would have been. The calm, focused and controlled testing environment seems a million miles from the context in which real people would have experienced Protect and Survive. And the tests only checked whether people retained information; no practical tasks, such as shelter-building, were undertaken by the test subjects. Add to that the insistence in internal memos that the campaign should reinforce the “stay at home” message, and one could infer that the campaign was more about preventing panic than actually offering practical measures householders could take. I’ll come back to this point in the next post in this series.

The finished article

The campaign came in at a cost of £108,000 – around £1m in 2017 prices – with the Home Office paying £96,000, and HMSO (the Stationery Office) making up the difference. Home Office documents suggest this compared favourably to the cost of other contemporary campaigns. Had they actually had to launch the campaign, it would have cost a lot more, thanks to the need to purchase newspaper advertising space – and, of course, print and distribute booklets to millions of households.

The booklet existed, but received extremely limited distribution. F6 Division made clear from the outset that, unlike previous booklets, the Protect and Survive one “would not be sold over the counter” – because, as discussed earlier, Protect and Survive was unlike previous booklets. Around 2,000 were printed in this first run. Three copies were sent to every local authority: one for the chief executive, one for the county emergency planning officer, and one for the officer designated as wartime country or district information officer. Chiefs of police were also issued with the booklet. A circular included with these copies made it clear that no further booklets would be made available.

And, for a few years, that was that – until, in 1980, Protect and Survive was thrust back into the public eye – something I will look at in a future article…

Looking for more?

My book, Nuclear War in the UK (Four Corners Books, 2019) is packed with images of British public information campaigns, restricted documents, propaganda and protest spanning the length of the Cold War.

It also tells the story of how successive UK governments tried to explain the threat of nuclear attack to the public. It costs just £10 – find out more here.