Shortly after the Second World War, with the partition of Germany into four Allied zones, the four former allies – Britain, the US, France and the USSR – set up ‘military liaison missions’.

These diplomatic organisations were designed to encourage dialogue and understanding between the powers now operating within Germany. In reality, they ended up providing the perfect opportunity to carry out intelligence-gathering missions in plain sight.

The British and Soviet missions, BRIXMIS and SOXMIS, were the first to be established with the Robertson-Malinin Agreement on 16th September 1946. (Officially, BRIXMIS was the British Commanders’-in-Chief Mission to the Soviet Forces in Germany, but that’s a bit more of a mouthful.)

The French and US militaries also set up their own military liaison missions, known as La Mission Militaire Française de Liaison – MMFL (or FMLM in English) – and USMLM. However, BRIXMIS was bigger than both, and the exploits of BRIXMIS and SOXMIS played out as one of the more curious stories of Cold War diplomacy.

Legal spies

To begin with, BRIXMIS and the other missions were involved in important post-war clean-up work, such as bringing prisoners-of-war home, hunting down war criminals and policing the black market. As these operations became less pressing, the missions shifted their focus to the activity that would characterise them for the rest of the Cold War: intelligence-gathering.

As part of the set-up of the military missions, members of each mission had special rights to cross the border and travel about – with very few restrictions on where they could go. Both BRIXMIS and SOXMIS took full advantage of these unusual privileges, regularly sending their highly-trained members on tours of the other side in specially-adapted diplomatic vehicles.

They would frequently push the limits of diplomacy, driving into restricted areas, photographing military installations, and taking careful notes of any troop or equpiment movements.

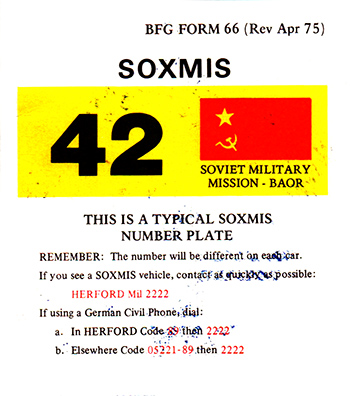

Although they did their best to keep their visits under wraps, both sides were obliged to display a special diplomatic license plate. That meant any opposing soldier could spot a BRIXMIS or SOXMIS crew where it shouldn’t be, and take appropriate action – if they could catch the vehicle before it fled back to safety.

Avoiding diplomatic incidents

Everyone had to tread carefully: the missions were based on a diplomatic agreement, and both sides valued the ability to travel around the other’s territory. And, of course, this all took place on the potentially volatile front lines of the Cold War. Mistakes and misunderstandings had to be avoided at all costs.

To that end, British forces in Germany were issued with cards instructing them on how to behave if they spotted a SOXMIS operation underway. These cards, known as BFG Form 66 (for British Forces Germany), seem to be as much about avoiding causing a diplomatic incident as they are instructions on the detention of hostile vehicle.

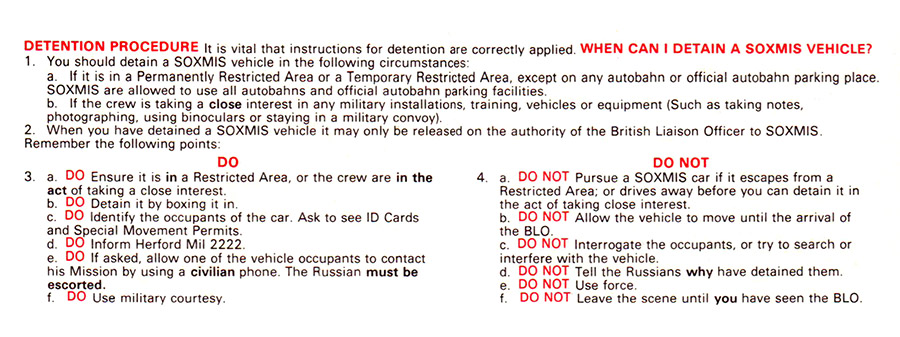

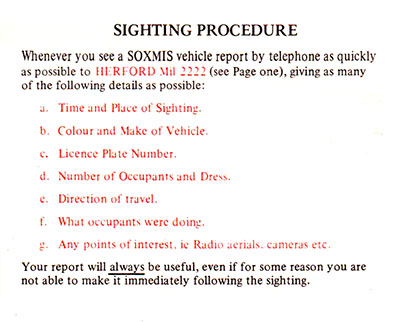

On spotting a SOXMIS vehicle acting suspiciously – that is, being present in a prohibited area, or ‘taking a close interest’ in military installations or activity – the card’s bearer is instructed to take immediate action.

They’re told to quickly contact a hotline, Mil 2222, at Herford, where there was a major BFG base – home to the British Army’s 1st Armoured Divison, as well as the German studios of BFBS, the British Forces Broadcasting Service.

There’s also lists of ‘dos and do nots’ – which boil down to ‘do identify the occupants and stop them from leaving’ and ‘don’t do anything that will spark a diplomatic incident’.

The cards pictured here are the revisions from April 1975 and June 1986. The later revision saw the card reduced in size, but the key messages were made bolder. The text was re-set in a sans-serif typeface, making it sharper and arguably more legible – essential where the bearer had to quickly read, understand and act on it in the field.

Keeping tabs on SOXMIS

After originally publishing this blog post, I was contacted by Tom Murphy. Tom served in the British Army’s Intelligence Corps during the Cold War, and in the mid-1980s was posted to JHQ Rheindahlen – then headquarters of the British forces in Germany – to Intelligence and Security Group (Germany), where, working in counter-intelligence, he was on the receiving end of information about SOXMIS. He says:

“We had various overt and covert assets under our control, one of which was 28 Intelligence Section based in Herford. 28 Int Sect was our covert surveillance section, and SOXMIS was their main target.”

“Most people thought that the telephone number on the BFG Form 66 was either the Royal Military Police or the British Liaison Officer. We were happy for people to think that, but the number was actually manned by the duty NCO at 28 Int Sect.

“One of my jobs each morning was to receive an encrypted teleprinter message from 28, giving details of their surveillance from the previous day and also any reports received on Herford Mil 2222. Then I would plot them on a map of Germany and try to work out what they had been interested in on that day. I would compile a weekly report that the section OC would include in his weekly brief to the C-in-C BAOR.”

Many thanks to Tom for this fascinating additional insight.

Find out more

The military missions operated throughout the Cold War, with business as usual even continuing beyond the fall of the Berlin Wall. Their mission officially came to an end on Germany’s reunification.

You can discover the full story of the military missions in Tony Geraghty’s detailed and compelling book, BRIXMIS.

There’s plenty more information and photos available over at the BRIXMIS website. You may also be able to listen to the Radio 4 documentary, The Brixmis Story, on the BBC website.

Looking for more?

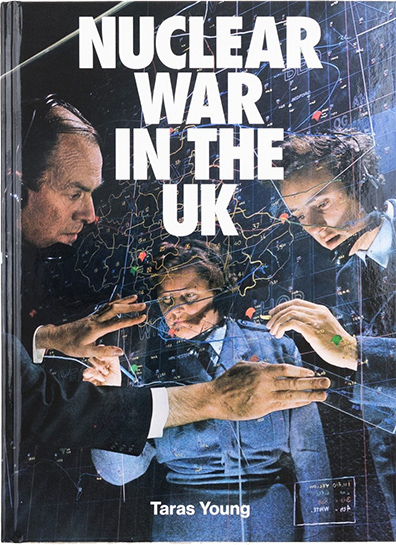

My book, Nuclear War in the UK (Four Corners Books, 2019) is packed with images of British public information campaigns, restricted documents, propaganda and protest spanning the length of the Cold War.

It also tells the story of how successive UK governments tried to explain the threat of nuclear attack to the public. It costs just £10 – find out more here.